The Dakar Rally Raid: The adventure began back in 1977, when Thierry Sabine got lost on his motorbike in the Libyan desert during the Abidjan-Nice Rally. Saved from the sands in extremis, he returned to France still in thrall to this landscape and promising himself he would share his fascination with as many people as possible. He proceeded to come up with a route starting in Europe, continuing to Algiers and crossing Agadez before eventually finishing at Dakar. The founder coined a motto for his inspiration: “A challenge for those who go. A dream for those who stay behind.” Courtesy of his great conviction and that modicum of madness peculiar to all great ideas, the plan quickly became a reality. Since then, the Paris-Dakar, a unique event sparked by the spirit of adventure, open to all riders and carrying a message of friendship between all men (and women), has never failed to challenge, surprise and excite. Over the course of almost thirty years, it has generated innumerable sporting and human stories.

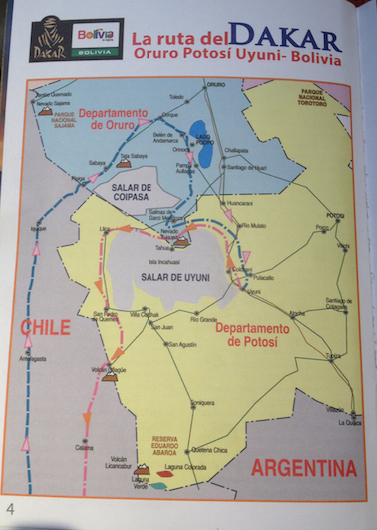

The only way to complete the Dakar is through a combination of endurance and determination. The competitors will have an additional problem to resolve on the 9,000 kilometres to be covered in Argentina, Chile and Bolivia: adopting and maintaining the right momentum, while the route continuously endeavours to break it. Depending on the day, both the setting and the pace will change, moving from rocky routes to desert dunes and from endurance stages to extreme sprints. Given the competitors’ inability to recognize clearly identified sections, in particular they must capitalise upon their ability to adapt and to control their stamina. The marathon stages will definitely remind them of this basic rule of off-road races.

The Dakar tests competitors and their vehicles in extreme endurance. The marathon stages, where drivers cannot use their assistance teams, are a particular test of their ability to independently manage their mechanics. This year, cars and trucks, which have not taken part in a marathon stage since 2005, will have to tackle this additional difficulty. Split over two days, a marathon stage involves some of the competitors spending the night in an isolated bivouac. The vehicles are taken into a closed area, where only help between competitors is authorised. Despite the technical challenge that this constraint represents, the drivers also enjoy a different, highly convivial atmosphere. In Uyuni, it will be the car teams which will spend a night apart, followed by the motorcyclists and quad bikers the next day. The truck category will have its own dedicated bivouac in the middle of the Atacama Desert.

For several years now, the organisers have used their in-depth knowledge of the South American terrain to refine the routes and offer specific features for each category. For the 2015 edition, the motorcyclists and quad bikers will face an additional difficulty, with a particularly dense second week: four marathon days in total. 35% of the kilometres they cover without the cars and trucks will be in the form of special stages.

Our days at the Dakar, Bolivia

The seventh stage of the Dakar Rally at La Chita saw us watch an afternoon of cars bomb through the sand, braking momentarily only to register at the checkpoint. The sun, a white hot penny in the morning turned to lightning-charged skies by the afternoon. Lashing rain down on the racers and spectators dampened not a single person’s spirit. Witnessing history being made, right in the thick of it left me tingling from the inside out.

Newly but well-acquainted with the Bolivian blokes, the show for them had come to an end. Alas, they packed up their seven-tonne lorry to return home. Despite the inclement weather of iron-grey clouds and a sand storm in full swing, there was no way we’d be following suit. The biking warriors were due to race through La Chita the following day. But with the passing of time, and the departure of its main characters, the resultant mixture felt denuded and flavourless, like meat with the goodness boiled out of it. Overly inquisitive wide-eyed faces on legs started swarming towards the bikes. Without the protection of our makeshift compound in which we’d been ensconced, it was a tad intimidating to witness inebriated men succumbing to a strong urge of clambering all over our bikes like a climbing frame in a child’s playground.

As with all good books, every page is un-put-down-able. Just as one chapter finished for us, the next started. A new dawn, a new day. Darting my eyes wildly around the site, I glimpsed a rather impressive expedition truck. A Unimog. I rapidly developed an abiding interest in its owner. A man was leisurely sat on his deck chair, shaded by an umbrella on the roof atop his all-wheel drive, all-terrain truck. A robust thing, which had a ground clearance of about a metre, the tyres looked like they’d been extracted from a tractor and it had a distinctly lock-down air of security to it. We’re talking: extreme torsion resistance, a welded frame, fording ability, coil-sprung axle suspension and stable portal axis with a hydraulic system. Go figure, the Germans know good engineering. It came as no surprise when a passing American girl ventured over, the cogs turning as she was trying to process the image of this vehicle before her. After a few moments, she smiled and remarked, “So like, I guess this is what? An intense trailer?!” I guess so.

Meet Franz and Ingrid, a retired couple in their fifty-something prime of their lives. Travelling to their hearts’ content. Franz spoke with a fierce and urgent vividity, his blue eyes shining as he brought the subject of travelling through foreign lands into sharp focus. He regaled us with his truck-bound journeys; as a skilled storyteller, his vocation offered a deep resource for some forthcoming tales. He remained humble about the Unimog yet nostalgic when he clocked our bikes and the ticket to freedom that two wheels bestow. The couple was as gracious as they were generous towards us. The pleasure was all ours. Retreating the tent and our somewhat exposed motorcycles under the safety of the dominant Unimog, we’d found our new home for the next stage of the Dakar.

Armed with sunglasses, sunscreen, cameras and waterproofs, we headed off to spend a second day under lightning-charged, bruised skies. The first batch of 30 dirt bikers descended. Including female rider Laia Sanz, her ponytail bouncing up on every corner as her wheels left a spectacular sand cloud in her wake. Respect! I blinked in shock from the insanely close proximity we were from the racers as much as the dust. Crowds either side were no further than around two metres from the action, edging closer as each rider zoomed into view. Only in Bolivia…!

Army recruits were too interested in the race to mind about something as trivial as folks running across the track every three minutes. Taking selfies and filming, cheering on the crowds and purchasing sunglasses seemed to be the order of the day for those in khaki uniform. For every adult man, I clocked nine boys of pubescent age. A total lack of organization and safety, at least no one was hurt for the fortunate part. What a sight! The official Dakar programme informed readers how Bolivia will – like the previous year – once again “amply satisfy” all requirements of the rally’s enterprising organisation. Definitely the land of stark contrast, colour and crazy.

Rooting specifically for two riders, a father and son duo Simon and Llewelyn Pavey – we waited for their eminent arrival – numbered 76 and 75 respectively. Through intense sunrays, which gave way to a dramatic purple sky, thunder and lightning played their part while we continued to watch and wait. Hours passed. Each time I examined a rider’s identifying number, a bit of the excitement dispersed, like a pool of shimmering water that evaporates beneath the midday sun.

I didn’t want to but couldn’t help wonder if our Aussie shining stars, usually residing in Wales were still in the race. Of course they were, despite a couple of crashes and nasty encounters with dehydration, altitude sickness in -9 degrees Celsius conditions and dizziness requiring oxygen and a drip en route, the boys were faring incredibly well. Their official website and social media were keeping us well informed by the hour. More time passed and a relentless rain began to fall. Temperatures plummeted and the thought of a hot drink to revive the cockles settled on my mind like a nylon cloth and wouldn’t let it breathe.

Killing more clock towards the back end of a cold, drizzly afternoon, we finally retreated to the coziness of the Unimog. There was a lull of riding anyway where only the odd quad and biker caught our attention sporadically. Then Simon and Llewelyn came through. Triumphantly passing the seventh stage. It was a moment of pure elation for us; it must have been euphoric for them. And relief mingled with chronic exhaustion probably. I waved my arms crazily, like a trapped moth in the hope of attracting their attention. I was too far away and felt my body crumpling under the shame of not being closer, like a sheet of newspaper burning in the fireplace. All night, the thought of catching them on the morrow niggled away at me. I would not let these men down through their heroic marathon.

A night of torrential rain left the tent bobbing in a lake by morning. Not an ideal start but not a deal-breaker either. We packed the tent down in record time, said our Auf Wiedersehens to our Deutsch freunds and headed straight to the Salar, the start of the next stage. The road under construction was slow going but made easier by filtering routes back onto the intermittent hardcore. It enabled us to claw back a bit of time, a small boon at least. Pearl’s never been one to relish the wet, this occasion was no exception. Pray old girl, just get me to the Salar. Putting my selfish needs before her own, I ignored the sluggish movements of my trusty wheels and sighed in resignation when Pearl put her foot down. Going nowhere, not least the eighth stage of the Dakar.

Five miles from Colchani, I studied my options as I surveyed the scene. I could abandon Pearl and ride ‘two up’ on Jason’s bike. Or perhaps push my motorcycle through the mud bath of slippy dirt. Out came the towrope. It was wet, the ground was squidgy at best and the puddles the size of paddling pools at worst. It was actually quite good fun once I got into it and picked up the technique without any snotting and screaming. “You did well today”, Jason surmised as I detected just a hair of relief in his voice. “Thanks!” I responded, without keeping the relish out of my voice. Riding side-by-side or in our case ‘subframe-rope-to-foot peg’, we gained independence and proximity. Motorcycling will leave you dizzy with a sense of liberation. All you need is an open mind and a cast-iron gut.

Jason rumbled Pearl back into action at a gasoline station while I chuckled that we were splattered helmet-to-boot-tip in mud. My hair had taken on the texture of straw and I was sporting black rings around my neck, which complemented the thick streaks of black embedded under each fingernail. A by-product of having too much fun in the desert over four days with no facilities. Without delay, we bobbled over the corrugations and squelched through the mud onto a wet Salar de Uyuni.

We were too late. Cars were inching away from the Salar while we pushed towards it, refusing to believe we’d missed the start. It had gone 9.30am, of course we’d missed it. Officials were turning traffic away from the Salar, assuming everyone had had their Dakar fill. What left me so royally out of favour with myself is that had we pressed on a further five kilometers onto the Salar to the worldwide collection of flags were located and well, not broken down, we would’ve caught the the riders leaving the salt flats. Our good intentions had turned into a complete debacle! The odds were stacked against us, we’d missed the boat and the bikers. Life would invariably continue, the rain would carry on falling and I suppose I was resigned as the Bolivian beggars who sat outside most city street corners, my hands outstretched.

Bolivia, I’ll say again, is the land of contrast. Her sun is devilishly hot but when she feels capricious, she’ll banish all warmth to be replaced by golf ball-sized hailstorms come the afternoon. She’ll give you strong WiFi but weak sanitation. You might think the local drivers who appear kamikaze – compared to those in Argentina for example – are out to kill you; they’re not, they’ve just never had to take a driving test on a par to British standards. Every street corner you’ll see 19th century bowler-hatted women clad in a silky shawl, llama-wool cardigan and traditional pleated skirt walking alongside their children donning ‘Ben 10’ tracksuits and Nike trainers. In front of them lies a mirage of commerce amid barminess – changing every paradigm and preconceived idea of the place you ever had. There is even an ineffable grace in the midst of squalor.

The start of second stint in Bolivia was far from brutal compared to the initial experience. My efforts to tune into the country during the first time round felt phoney and misguided. By the country’s own volition, this time was brilliant fun; connecting with the locals left me giddy with a sense of warmth and magnanimity only fellow motorcyclists seem to share. The friendship, fond regard and affection that only riders and their motorcycles can ever know, we humbly reaped the rewards of camaraderie that is the fellowship of the road. Like a kaleidoscope, Bolivia had shaken me and settled my pieces into a different arrangement.

Thanks to SP Fifty One for capturing fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants action shots of Simon and Llewelyn Pavey.