Having learned it was “bubble net” season for a short spell sporadically through the summer months, and hoping to catch the tail end of it—no pun intended—I unearthed that such a phenomenon only occurs in Southeast Alaska by an elite few. Indeed, there was no time to lose in catching the ferry to the state capital and book on the next available whale watching tour with Juneau Whale Watch.

Happy to leave Haines on the Alaska Marine Highway and dry off a little, if not to escape a somewhat passive aggressive campground host whose words were beginning to fall on me like hot oil. Mmn, there’s no currency to straighten a warped spirit, or open a closed heart. With my mood somewhat dampened, it was time to get our whale on again. I could always rely on these remarkable gentle giants to radiate gladness into my soul.

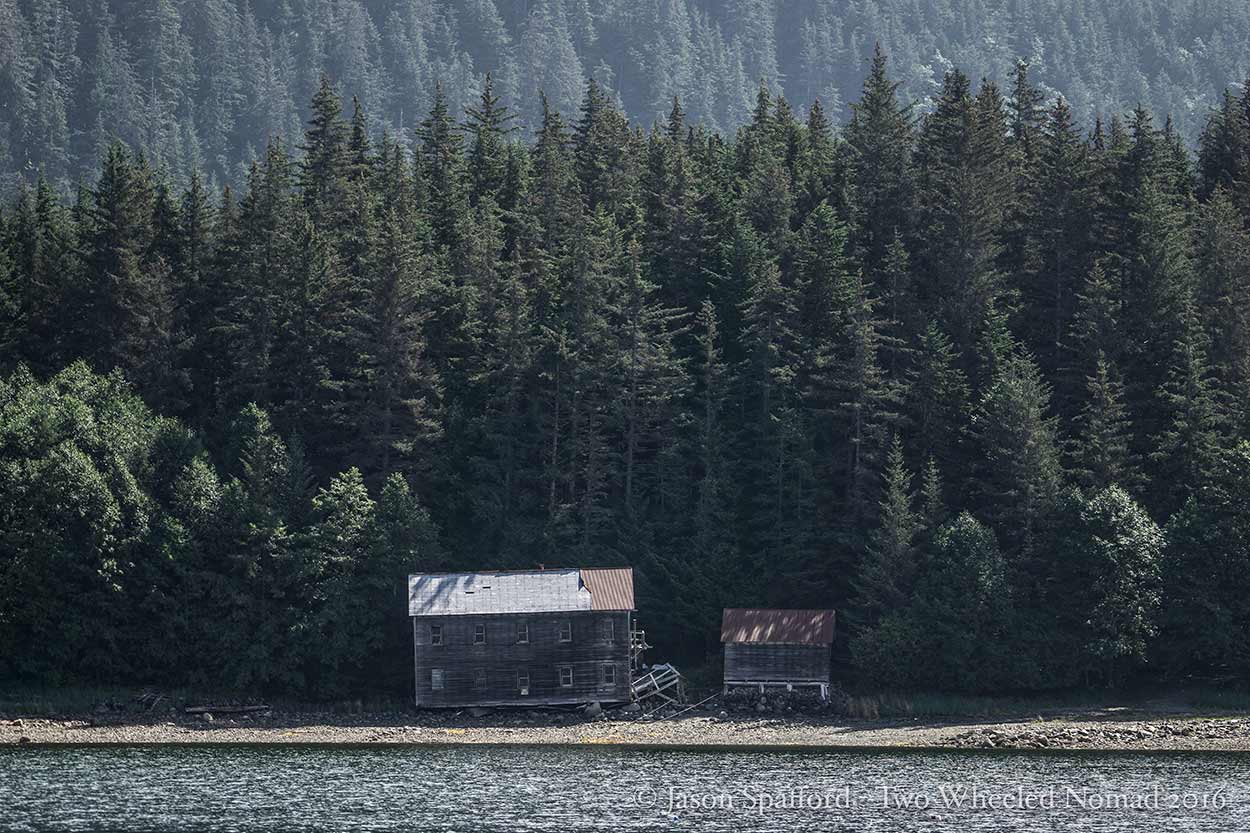

Juneau is many things. Think: primeval in its setting as much as enchanting, Juneau is tranquil. Effortlessly and without pretense, it invites you to become engulfed in its otherness. Perhaps most appealing, the coastal city, which sits in the state’s panhandle, is nestled in a mist shrouded, temperate rainforest. Bound by an Icefield of glaciers on one side and water on the other. Often, an early morning fog seems to silence the dense greenery, while the bald eagles soaring overhead blend with the rippling sounds of the nearby creeks and babbling brooks. If that’s not enough, the speck-sized haven boasts more miles of trails than miles of road. What in the world are we waiting for?

On top of all that, Juneau is endowed with copious wildlife: more animals than people. Many of these natural wonders abound in Juneau’s sparkling waters: humpback whales we hear sometimes bubble net feeding; pods of orcas and dolphins; sea lions basking in the sun; and bears roaming by the creeks filled, at this time of year, with a smorgasbord of spawning salmon. A sublime watery wilderness all below a sky’s worth of bald eagles. It’s a recreational paradise for all on top, as well as a cultural jewel rich in Southeast Alaska Native heritage. Not too shabby for a tiny oasis of civilization. Simply, it’s more of the magnificent on offer in Alaska.

So what in the world is bubble netting? In a nutshell, it’s a unique and complex feeding strategy employed by certain humpback whales that come to Juneau’s protected waters in Southeast Alaska. Ordinarily, humpbacks are solitary creatures that travel alone. The bubble-netting behavior sees a group of humpbacks come together, and rapidly circle in an upwardly shrinking spiral. All the while blowing bubbles beneath a school of fish, commonly herring—teeming the waters in the summertime. The herring get corralled into the net, produced by the baleens’ precise, fine-scale movements and finely tuned teamwork. NOAA (the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) studies delve into the fundamental whys and fascinating wherefores.

Having the help of another Juneau Tours boat tip us off, Jason—our jovial and quick-witted captain—deposited us in the right drop of ocean. The staff on board helpfully deployed a hydrophone, enabling us to incline our heads and eavesdrop on the whales warbling their haunting, unearthly feeding call songs. Honestly, there’s nothing quite like listening intently to a baffling concert of cries, moans, squeaks, clicks and whistles. Perhaps foremost, the hydrophone aided us on where to direct our eyes, cameras and binoculars in anticipation of the remarkable activity. Although no underwater microphones were needed to hear the excited tonal blows, loudly reverberating off the water with every trumpeting exhalation.

Most humpbacks embark upon an annual 3,000 mile migratory journey from the North Pacific Ocean to Hawaii, Central America, Asia or Mexico to propel the circle of life and nurse in the wintertime. Very few are still found loitering in the cold waters of Alaska, Eastern Russia and British Columbia over the opportunity to vamoose, save for the popular period, which is undoubtedly during the summer months facilitating the replenishment of their stores. Feasting like royalty, who as a fully grown adult mother could average at 42 feet (12.8 metres long) and get up to 55 feet and 110,000 pounds.

When I saw the rare occurrence happen for the first time—never knowing exactly when and where it might arise—it was like watching 45+ ton apes of the ocean using tools. Observing a strategy of group cohesion take place before my very own eyes triggered a jaw-on-the-floor moment to say the least. The marine mammals coalesced in a jumble of glistening bodies, sounds, splashes and raw energy. Then they efficiently scooped up lunch with their mountainous mouths, gulping thousands of fish at once. It was over in a flash. Done. “Inspirationeering” sprung to mind upon watching such a feat of targeted teamwork but somehow remained a weak term for the actual spectacle.

The bubbles bounced on the surface like boiling water, that roiled to ensnare, dare I say, the unaware; pinching myself that such a production was being orchestrated by the cetaceans’ precise, fine-scale movements and finely tuned co-operation. It was a profound sight. When the complex behaviour happened a second time on the same tour, I just about erupted in a rainbow of emotion. As unparalleled firsts go, this one teetered on perfection. The boatload laughed, punched the air, high fived the person closest and whooped like they’d never heard the word “worry”.

Jason (my partner, not the captain), returned from another tour having witnessed the exceptional event no less than 12 times, whoa! As for theories of conspiracy and the most unpredictable behaviours, surely they’d cornered the world market on those. I guess happened-had-happened and be-will-be as far as the whales feeding were concerned.

Bellies full from a summertime feast, having practically unhinged their jaws to guzzle seafood by the truck load, an impish expression often times stole across the faces of Juneau’s gentle giants. Especially when they decided to play, spy-hop (poking their head vertically out of the water to survey their surroundings), roll, fin-slap and tail lob right by the boat to our delight.

Up next, the captain received word over the radio by a fellow captain and navigated us towards a family of orcas. Commonly known as killer whales, orcas aren’t really whales at all: they’re a species of dolphin. But playful like Flipper the friendly dolphin they’re not. Orcas rank among the blue planet’s most adept predators, their true hunting spirit known to take out semi-submerged moose, whales, even great white sharks!

Although in Juneau, the monochromatic beasts love to dine on the local salmon, who wouldn’t? While more elusive than the humpbacks, the killer whales are very distinctive: a male’s dorsal fin for example can reach lofty heights of up to six foot. Bestowed with both resident pods and transient pods, the nomadic creatures often clock up to 100 miles in a single day. Our luck was in, it seemed. And it was no surprise to learn that the natives revere such marvels of the ocean, depicting them heavily in Southeast Alaskan culture.

Booming down his microphone and radiating oodles of enthusiasm, Jason (the captain) pointed at 9 o’clock to the black magic carving through the water. Two fully-grown adults and a handful of calves cut gently through the water, unperturbed by our peripheral presence. Always at a respectful distance with the engines off. That said, with the motor killed, the whales cared little and less about us watching intently; too busy feeding their faces. It gave rise to a calm atmosphere that the attendance of humans was neither encroaching nor impinging upon such an important time for the whales.

The exquisite wildlife, matched by the naturalists on board—who were gregarious as much as hilarious—sought to give us a privileged encounter. Altogether, they put the frosted icing on the Alaskan cake and gave my soul a lifetime’s worth of sunshine to dine out on.